A Cut Above: Bugisu Boys Become Men

At seven o’clock in the morning, the circumcision procession reached our house. There was no question of staying in bed; the villagers expected us to attend. We followed the crowd through the village, not entirely sure of what was happening. Everyone had been talking about circumcision for weeks, but no one had explained exactly what to expect. By the time we reached the border between our district and the next, most of the village was present, dancing and stamping along the dirt tracks. They seemed very pleased to have us there. Several people came up to us and said, ‘This is our culture. Now you see Bugisu culture’.

At the front, a tight group singing tribal songs had formed around Benedict, the boy who was to be circumcised. In the middle, Benedict himself danced almost frantically, leading the singing, although he was clearly exhausted.

After walking for over an hour, the circumciser took Benedict to a river and doused his penis with water. We carried on through two more villages before coming to a halt outside a house. The crowd formed a circle, into which Benedict danced. Suddenly everyone was pushing and craning to see the cutting. I couldn’t see the circumciser, but I could see Benedict’s face throughout. He stood perfectly still, holding a stick behind his head with both hands. He didn’t flinch or blink while the circumciser worked. Later I was told that he ‘stood well’, which was a very good thing: boys that show fear or pain risk being killed by the men of their village. When the cutting was finished, everyone cheered and women started to dance and sing. Someone found a chair and sat Benedict down. He was shaking but clearly pleased; he knew he had done well, and from that day on, he would be a man.

Benedict had undertaken Imbalu, the Bugisu tribe’s circumcision rite, which is celebrated in the Bugisu lands of eastern Uganda and western Kenya. For the men of this tribe, their identity as Bugisu is defined by the circumcision rite, marking their passage into manhood. The actual cutting and procession are only small parts of a complex ritual which involves almost the whole community.

Circumcision takes place after puberty, but the boy himself chooses the year in which he will be cut (though often with a lot of parental influence). Weeks, even months, before the circumcision, the boy will start practising his dancing with an entourage of children and teenagers. The dance culminates in a series of wild leaps in front of a respected person who then gives the boy a small amount of money or warns him about the difficulty of the ritual he is undertaking.

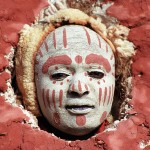

Every village has its own circumcision day. Three days before the ceremony, the boys that are to be circumcised prepare a mixture of maize flour and yeast that will be fermented into malwa, a local beer. The boys are then smeared with maize paste before dancing through the village centre in ceremonial dress. The whole village comes onto the streets to celebrate. The boys dance almost continuously and are denied sleep. By the third day, they are exhausted and the malwa is ready to drink. The beer is sprinkled on the ground as an offering to the ancestors before the boys dance to a bog where they are covered with mud. They then return to their fathers’ homes, where the cutting takes place.

The significance of Imbalu to the Bugisu is hard to exaggerate. The Bugisu believe that men are distinguished from women by their ability to experience lirima. There is no exact translation, but lirima can be considered a sort of overwhelming anger that allows for forceful and determined action. Imbalu is the first occasion on which a boy is expected to experience lirima, proving that he is a man. During Imbalu, the boy must display lirima through courage and determination; he must continue with the preparations despite being warned of the pain and difficulty, persevere through sleepless nights of dancing, and show no pain when he is cut.

Once a boy has been circumcised, he receives the rights of a man: he will be given a house and land, he may marry, and he may drink beer. The Bugisu are known throughout Uganda as a tribe of circumcised men; if a boy refuses circumcision, he will be denied full recognition as Bugisu. It is relatively common for men who have not undertaken Imbalu to be forcefully circumcised or for their bodies to be circumcised before burial.

The Bugisu believe that the Imbalu ritual has been practiced for thousands of years, and unlike some other practices, there has been no attempt to stamp it out. The nearby Sabine tribe practice female circumcision (female genital mutilation or FGM), and have faced pressure from the government and NGOs to end the practice. However, no similar attacks have been made on male circumcision. Since independence, Uganda’s governments have left Imbalu alone. The Church and human rights organisations have likewise remained silent on the issue.

But should male circumcision be discouraged? Strong arguments can be made for condemning Imbalu as a human rights violation. The ritual certainly draws parallels to FGM, though the chance of permanent damage is much lower. It is a painful and traumatic procedure in which considerably more skin is removed than in circumcision operations performed in the West. Although the boys have some say in when they are circumcised, they have no choice in whether or not to undergo the procedure. The only way to permanently avoid the circumcisers is to leave the tribal homeland forever, which is not a realistic option in a society characterised by tight family bonds and very low incomes. However, even if the boys could choose not to undertake Imbalu, it seems unlikely that many would. The boys appear to look forward to their circumcision and take great pride in ‘standing well’. Measures are taken to reduce the risks involved. The circumcisers, or ‘local surgeons’ as they are officially know, must carry certificates their qualification. The knives are clean, and medicines are provided for the boys after they are cut.

If it is decided that Imbalu violates human rights, it seems unlikely that outside condemnation could do anything to prevent it. Moses, a Sabine man, said that work to end FGM in his tribe has only pushed circumcisers further into the hills and forests, despite some official claims to the contrary. It is likely that similar efforts among the Bugisu would produce the same result. Circumcision is so much a part of Bugisu identity that external pressure to end the practice would be fiercely resisted.

However, change may be coming from within the tribe itself. Bernard, who is from a relatively wealthy and well-educated Bugisu family, was circumcised in a hospital. He is proud to be Bugisu, but he is against Imbalu because it ‘has no purpose’ and can be dangerous. Bernard believes the ritual demonstrates the ‘backwardness’ of his tribe, something he hopes to overcome. While circumcision remains central to the identity of some Bugisu, Bernard is part of a new generation that are finding ways to be Bugisu without Imbalu. With rising levels of education, it seems that the days of Imbalu, with all its colour, vibrancy and violence, may be numbered.