In the spirit of welcoming the summer months, when Oxford students emerge from classrooms and college libraries to bask in long-awaited sunshine, this issue of The Oxonian Globalist casts light on activities that are normally enveloped in shadow.

Each day, the forces of supply and demand funnel a bricolage of goods, services and migrants across international borders and around the globe. Too often, the long arm of the law is mercilessly overpowered by Adam Smith’s invisible hand. In these cases, regulations that govern production and exchange are powerless to hold back the torrent of market forces. As a consequence, beneath the surface of the visible economy, a thriving clandestine market facilitates trade between buyers and sellers.

In this issue, our authors examine a myriad of underground activities. In Colombia, calls from abroad for a moratorium on the production of coca have, ironically, caused the market for cocaine to flourish. Conversely, in Bulgaria, the illegal antiques trade could and should be quashed with stronger legislation. Allegations of organ harvesting in Kosovo, as well as botched executions in the United States, suggest that unregulated trade can perniciously violate personhood. Equally, a shortage of sepulchral storage in Hong Kong implies that underground markets continue to wield power even beyond the grave.

Since our Hilary edition, the world has undergone some rapid political transformations. Articles in this issue confront the impact of the Arab world’s spring awakening, the violence surrounding Nigeria’s turbulent elections, the art of imprisoned dissident Ai Weiwei and Britain’s controversial healthcare reforms. We hope you enjoy this issue. Please let us know what you think by dropping us a line at [email protected].

Thank you for your interest,

Sahiba Gill, Managing Editor (Print Edition)

Mark Longhurst, Editor-in-Chief

]]>

Chilean Miners. Illustration by Leila Battison.

WHEN all 33 Chilean miners were released from the San José copper mine in October 2010, after two months of entrapment, the world rejoiced over the happy ending to the story they had followed throughout the summer. But the findings of an official investigation of the San José disaster – released in March – suggests that the case has more sinister beginnings than its ending would suggest.

The report blames the owners of the mine, Alejandro Bohn and Marcelo Kemeny, for failing to put in place the health and safety regulations required by authorities. In fact, the company had been repeatedly fined for ignoring these safety rules in the years before the disaster. But that immediate cause was, in turn, facilitated by the absence of regulation enforcement – something the government version of events conveniently omits. Until now, there have been only three inspectors responsible for the 884 mines in the mining-dominated Atacama Region, which covers San José. Chile is the largest producer of copper in the world, and so while the large corporations that drill for copper comply with international regula- tions, many smaller mines – like the one in San José – fall between the cracks.

Invisible Mines

Chile’s safety standards are among the most stringent regulations in the world. According to Andrew King, national coordinator for health and safety at United Steelworkers, an American trade union, the “safety standards [that] companies are supposed to adhere to are as good as in the US and Canada”. Indeed, big private mines owned by international giants like BHP Billiton, Anglo American, Barrick and Xstrata enforce the same standards in Chile as they do anywhere else. The mines run by state agency Codelco operate with similarly high safety standards. Regulation enforcement falls apart at the micro level, where small private mines, many of which are unauthorised, operate beyond the reach of safety legislation.

In 2009, the latest year for which figures have been published by Sernageomin, the state body tasked with regulating the mining industry, there was one death in mines with over 400 miners, but 13 fatalities in those employing fewer than 12 people. One reason for this difference is economies of scale: large mines can profitably employ technology that reduces the need for people to be put in dangerous situations, such as trucks that transport materials to the earth’s surface. Small mines cannot. Small mines are also more likely to be owned by unscrupulous entrepeneurs looking to make short term profits when prices rise. The aforementioned report criticised the owners of small mines for prioritising profits over the safety of its workers. One of the authors of the report said that Bohn and Kemeny “wanted to replace safety and increase their income, [and that] this is not only inhumane but it is unacceptable”. Price spikes further incentivise irresponsibility; the most dangerous year for Chilean miners, 1999, coincided with the highest copper prices in recent history.

Invisible Hand

In response to the report, President Sebastián Piñera criticised the state regulator Sernageomin for its infrequent inspections of mines in the area around San José. In response, Chile’s Minister of Industry and Energy, Laurence Golborne, has instated a new director for Senageomin. The organisation’s jurisdiction has been expanded, and its budget, accordingly, has increased by 62%. Finally, Golborne announced plans to increase the number of national inspectors from 18 to 45 and train thousands of monitors as an additional measure for securing compliance.

Yet he has also told journalists that putting these plans into action takes time, and no evidence has emerged that any new inspectors have actually been appointed. In addition, Piñera has not fulfilled his promise to ratify International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 176, first passed in 1995. This convention requires states to consult with employers and workers in order to formulate, carry out and periodically review a coherent policy on safety and health in mines and develop provisions in national laws and regulations to ensure implementation. However, ratification in the near future seems unlikely. Former Chilean Minister Camila Merino has recently stated that following the general principles of the ILO directives was more consistent with the government’s objectives.

That skittishness towards regulation originated with Chile’s historic commitment to the Washington Consensus, a doctrine of deregulation, trade liberalisation, privatisation, tax reform, and fiscal discipline encouraged in Latin America by Bretton Woods during the 1980s.

The Chilean state – present government included – has traditionally seen flexible labour markets as key to eco- nomic prosperity. Even under the previ- ous Bachelet government, far more left than the current administration, the union representing the San José miners lost a legal battle to close the mine on safety grounds in 2003.

Chile’s refusal to ratify the ILO convention provides mining companies with perverse incentives. The ease with which firms can hire and fire temporary and agency staff leads to poor working conditions and increases the incidence of workplace accidents among poorly trained employees. The doctrine of limited regulation and anti-unionism negatively affects workers in all sectors of the economy. In Chile, almost 200,000 people suffered workplace injuries in 2009 and another 443 people died. María Ester Feres, director of the private Central University of Chile’s centre on labour relations, comments that “decent work is not a strategic objective of this country’s model for economic growth”. The now-famous San José miners are the newest victims of that policy. The government has stopped disability payments for 19 of the 33 San José miners, despite their ongoing complaints of physical problems.

The benefits of economic growth in Chile have not been spread equally among the country’s population, and the same ideology which limits regulation precludes government intervention to increase opportunities.

As long as people continue to be desperate for work, they will put up with poor conditions. Ratifying ILO Convention 176 could potentially improve the situation, but the Chilean government’s response so far suggests that this is unlikely. Preventing future disasters and protecting the most vulnerable requires consistent, proactive intervention, potentially at the expense of economic growth. That, in turn, will require a serious shift in the priorities of the Piñera government.

]]>

Source: Statistics Bureau of Japan

With a foreign population of only 1.7%, mostly from other parts of East Asia, Japan is arguably one of the most homogenous societies on the planet. Partly for this reason, Japan is in dire demographic straits. Japan’s life expectancy ranks, at 83 years, among the highest in the world, while the fertility rate, at 1.4 births per woman, ranks among the lowest. As the youngest members of the baby-boom generation hit 65 next year, demographers predict that Japan’s working population will be smaller than 1950 levels. Unless Japan’s pension age rises at pace with its ageing population, social security costs are set to rocket.

Japan’s naturalisation and immigration policies stem from a culture that in many ways promotes homogeneity as a virtue. This perception is perhaps most challenged by immigrants from the African continent. African migration to Japan, while small in scale, highlights the myriad of problems associated with Japanese immigration policy.

There are not many people of African descent in Japan – an estimated 30,000 in a country of 127 million, the majority of whom migrated from Nigeria, Ghana and Uganda. This paltry figure is, in part, a product of geographic proximity: Europe remains the top destination for African settlers. The hefty expense that accompanies the 13,700km journey or from Johannesburg and Tokyo renders Japan low on the list of the most expedient destinations for African émigrés. The ambitious young Africans who chose to migrate to Japan do so in order to seek study opportunities or experiences that will advance their career – factors that are more enticing when immigrants face persecution in their home countries. Journalist Jinichi Matsumoto estimates that 70% of Nigerian émigrés living in Japan belong to the country’s oppressed Ibo ethnic minority, many of whom sought immigration as a last-resort opportunity to achieve a better quality of life.

Language barriers and stigma severely limit employment opportunities for African migrants. While many legal immigrants may find well-paying jobs in the Japan’s robust manufacturing industry, the majority of Japan’s immigrants are undocumented male workers. These immigrants face few employment opportunities – many work unofficially in Tokyo’s entertainment industry, serving drinks to businessmen or serving as bouncers at nightclubs. Once in Japan, alien workers tend to avoid relocating for fear of attracting the attention of immigration authorities. Japan’s limited tolerance of underground employment opportunities pushes illegal migrants to the periphery of civic life. As a consequence, African communities are few and far between.

Japanese law reinforces this civic marginalisation. Although Article 14 the Japanese constitution prohibits discrimination of Japanese citizens on the base of race, social status or family origin, it does not distinguish between rights guaranteed for nanibito (everyone) and those reserved for kokumin (Japanese citizens). New arrivals from developing countries – derogatively dubbed sangokujin – are often attributed with a lower social status.

Additionally, the African migrant population presents disproportionate costs for the Japan’s healthcare system, particularly with regard to HIV treat- ment. According to the Africa-Japan Forum, Africans in Japan constitute for 25% of Japan’s incidences of HIV. The bulk of sufferers are uninsured and face an unenviable choice of forgoing treatment, or paying $16,000 for HIV medical care, compared to a more digestible $200 – 300 for those who are insured. Margaret Mawanda of Uganda’s Mildmay Hospital relays the story of a Ugandan migrant who, while detained by immigration authorities in Japan, was diagnosed with HIV and tuberculosis. During detention, the woman was not offered treatment, and as a consequence, her condition de- teriorated significantly. She returned to Uganda in a life-threatening condition. Over the past decade, the international media has reported a growing number of troubling incidents regarding the denial of treatment and health coverage for undocumented migrants.

If the current climate of discourse continues, solutions are unlikely to be found. In a Bloomberg interview in 2007, Tokyo’s governor Shintaro Ishihara asserted that “Africans…are there doing who knows what. This is leading to new forms of crime such as car theft. We should be letting in people who are intelligent”. The strength of Japan’s elderly vote, traditionally conservative, means any drastic shift in the government’s stance on immigration would likely be met with resistance. Pro-immigration policies similarly are unpopular with Japan’s younger generation, who fear that newcomers would place further pressure on unemployment.

Japan’s immigration policy is in dire need of reform. Over the next two decades, Japan’s rapidly ageing population will drain the country’s finances and slow the growth of a country flanked by prosperous emerging economies. In Japan, the sun is no longer rising. Greater tolerance to migrants from developing countries is one strategy the government can employ to prolong the sun setting altogether.

]]>

Illustration by Leila Battison, Worcester College

AT the time of writing, all eyes are fixed firmly on the Arab world. Ben Ali has been ousted and Mubarak has fallen. Next door, Colonel Gaddafi is lashing out at his own people in a last bid attempt to cling to power. The NATO coalition has decided to intervene in Libya in the hope that finally a number of Arab states, from Tunisia to Bahrain, will establish functioning democracies. So long as protesters continue to demand political change, the threat of instability will remain. This is a concern for the United States, which fears that riots may give rise to Islamic extremism. The war on terrorism was the justification for the United States’ continued support for Egypt’s US-friendly dictatorship. When Mubarak was ousted, the United States was concerned primarily about the risk of extremist parties gaining power in a democratic process.

Despite its purported support for the Arab awakening, the United States remains a power governed supremely by national interest, not humanitarian concern. This policy, though obscured somewhat by American intervention in Libya, is patently clear in the United States’ relationship with Nigeria. Nigeria has traditionally maintained stability at the cost of democracy, a strategy that has earned it a spot as the United States’ top ally in western Africa. However, Nigeria’s presidential election on April 16th 2011, has brought violence to Nigeria’s Muslim north, placing Nigeria’s stability in jeopardy.

Democracy Now?

Like the regimes in Egypt and other Arab states, Nigeria’s democracy falls short of the ideal. Since the end of military dictatorship in 1997, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) has dominated Nigeria’s political system. PDP has consolidated power by administering an informal party agreement known as zoning. The zoning agreement strikes a balance between northern and southern interests in Nigeria. Muslims in the north lack investment in agriculture and infrastructure, and fear political domination by the Christian south. The zoning agreement addresses the north-south political divide using a metronome model for presdientials elections: a northern Muslim president must follow a southern Christian president, and vice versa. On the one hand, the zoning agreement has served to protect Nigeria’s national elections from falling victim to sectarian divisions. However, the zoning agreement was largely engineered by Nigeria’s political elite, and the public has been excluded from approving this process of political horse trading. In recent years, Nigeria’s voting population has shown signs of increasing political indifference and disillusionment with the system. While Nigeria’s democratic process may be considered by some to be one of sub-Saharan Africa’s success stories, the reality leaves much to be desired.

When the previous president, northerner Umaru Yar’Adua, died in May 2010, he was replaced by his vice-president, southerner Goodluck Jonathan. Rather than stepping aside to allow for a northern Muslim candidate to stand for the ruling PDP, Jonathan chose to run for a second term of office. He won the party’s primaries in January, which was hardly surprising given that primary support usually flows to the sitting president, who has control over Nigeria’s vast oil and gas reserves. Having secured the party’s nomination, Jonathan emerged victorious from Nigeria’s presidential election. While experts remain divided regarding the implications of the election, some interpret Jonathan’s success as the end of the zoning agreement.

The United States has a key strategic interest in maintaining Nigeria’s political stability. Nigeria’s much-celebrated transition from dictatorship to democracy occurred in 1999 following 16 years of consecutive military rule. Since the transition, successive administrations in the United States have maintained a close relationship with Nigeria’s political elite. As a result, the oil-rich nation is now the United States’ largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the State Department, oil exports make up 90% of Nigeria’s GDP and 80% of government rev- enue. Nigeria’s economic growth relies heavily on the American oil market. In addition, Nigeria has often acted as a diplomatic intermediatory between United States and nations in the midst of political upheaval, such as Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. After 9/11, however, the United States sought to expand its political relationship with Nigeria in order to procure broad support for its anti-terrorism mission. Official statements from the United States sug- gest that Nigeria plays a “leading role in forging an anti-terror consensus among states in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In December 2007, Nigerian President Yar’Adua was hosted by President George W. Bush at the White House, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Nigeria on August 12th 2009 on her first official trip to Africa. Just as Egypt was a bastion of pro-West stability in the Middle East, so Nigeria is the same in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet that position was challenged last year when a Nigerian man attempted to blow up a plane over Detroit on Christmas Day. The United States promptly placed Nigeria on the State Department’s terrorism watch list. The day before the bombing, 32 people were killed in Jos while another six died in terrorist attacks on Christian churches in the north-east of the country. In reaction to the April presidential elections, Islamic extremism has reared its ugly head once more. While the perception that elections were fair and Jonathan’s victory deserved has prevented a full-scale war, Nigeria is not out of the woods yet. As The Oxonian Globalist went to print, more than 800 people had been killed in post-election violence, 300 of whom were buried in a mass grave. While Nigeria’s president may have been hand- ed a mandate by his people to govern, he will have to convince northerners that their interests will be represented in his and future administrations. As shown by the swift response to the Detroit bomber, countering the region’s potential threats to security remains a central concern for the United States.

The international community should rejoice that its efforts to ensure a fair election process in Nigeria have yielded success. However, the United States should remain concerned about Nigeria’s Muslim minority. If northerners continue to feel disenfranchised, their frustrations could provide the fuel that ignites future terrorist attacks on western soil. The primary concern for the United States is not the absence of a fair democratic process, but that its presence in Nigeria will threaten that country’s status as a partner in the war on terrorism.

]]>

ASER’s book publishing project provided the skill set needed to create a nationwide survey. Photo by Pratham Books.

IN India, the number of school-aged children enrolled in school is almost beyond improvement, with 96.5% of those aged six to 14 enrolled in school in 2010. However, that figure does not signify success for Indian education. In the same year, only 53.4% children 13 years old could read a text designed for seven year olds.

This figure comes from the ASER Survey, established in 2005 by Pratham India – the country’s largest educational charity. ASER manages to produce a highly accurate report each year, freely available to all, for just $1000 per state. Training and capacity building at every stage ensure that the survey adheres to strict statistical randomisation standards, and that each child is tested in the same way. The metrics produced are used by government and charities, but most importantly, by Indian citizens, who can now find out exactly where their 3% cess is going.

Before ASER, no national figures existed for the crucial early stages of learning; the focus was on enrolment. But enrollment is no guarantee of attendance, let alone achievement. Those children who fall behind early will seldom catch up: in classes of 50, teachers simply cannot attend to the needs of individuals. Such children typically fall further behind or leave altogether to start work early. Lack of resources, especially teachers, poor attendance, language differences between teacher and pupils, and policies such as placing children in classes according to age, not ability, contribute to making this occurrence a common one. Inadequate schools are even implicated in bonded child labour, since some parents in the grip of poverty feel that an ‘apprenticeship’ (for that is how such arrangements are presented) in a factory would be a better option for their child than a space on the floor in the back of a dusty classroom.

ASER began from a private charity, Pratham India, which has been addressing such issues for sixteen years, reaching 34 million children with just one of its many programs. Pratham’s main focus is supporting and training teachers. The ‘Read India’ programme trains teachers and volunteers in new techniques based on participation: maths is taught with a wide range of activities and reading with the Indian version of phonics – ‘ka, kaa, ki, kee, ku, koo, kay, kai, ko, kow’ – with speedy and impressive results across India. Pratham attacks the problem from every angle: combating child labour, setting up nursery schools, raising awareness and equipping libraries.

When they found it difficult to interest children in the small collection of story-books available, they even began publishing their own range of colourful, affordable children’s books which are now used throughout India. However, India is notoriously multilingual, with each region speaking a unique language. This makes creating tools a challenge: stories must be created that are equally easy to read in more than thirty languages, and several alphabets. Tools must be designed so that every volunteer uses them in a similar way. Pratham invested in solving those problems, and in doing so, learned the set of skills that would enable it to grow across India. As it expanded, reliable metrics on learning for the whole country became essential, and its biggest project yet – ASER – was born.

ASER is a survey both for and by the people. More than 100,000 volunteers have taken part over five years, testing 700,000 Indian children each year. Recruited locally, volunteers receive training then travel to their states’ rural areas, testing children in their homes. As the children attempt to read simple paragraphs, parents and neighbours gather, with an average of 25% of parents discovering that their child cannot read or add despite two years of lessons. Parents who themselves tend to lack basic edu- cation are often distant from their child’s schooling, and assume that attendance at school is enough. Surveyors spend time explaining their work with parents, the village sarpanch and panchayat (local leader and committee), who are often motivated to seek extra tuition (surprisingly common: 24% of children had some tutoring in 2010) or improve their local schools. Such tutoring can come from the surveyors themselves, who are often keen to ameliorate the inadequacies they were surprised to discover. Volunteers trained by Pratham run ‘accelerated reading schemes’ in thousands of villages each year, training children to read in just one month.

ASER represents a local approach to education that may be the key to educating India’s vast population. An educated child is likely to be healthier, wealthier, and have fewer children. For India, it’s a worthwhile investment.

]]>

Brazil’s current cabinet features a record number of female ministers. Photo by Angencia Brasil.

ON January 1st 2011, Dilma Rousseff made history by becoming Brazil’s first female president. Her landslide victory in Latin America’s largest election, with more than 130 million votes cast, represented a moment of triumph for women in South American politics.

Dilma defies Brazil’s female stereotype: the bikini-clad, hedonistic playgirl whose sensuous playfulness drives tourists wild. Instead, over the past decade Dilma has proved herself to be a competent Minister for Energy, a pragmatic economist, and a worthy political adversary. Her electoral victory is arguably as important for women in Brazil as Obama’s triumph was for African Americans in the United States.

Throughout the campaign, politicians struggled to adjust to the presence of a gifted female challenger in a political race that has traditionally been dominated by men. Prior to the election, then-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who supported Dilma’s candidacy, christened her the “mother” of Brazilian society. However, Dilma’s past involvement in Brazilian politics indicates that she should be characterised as anything but maternal. Like many latter-day Brazilian politicians, Dilma’s political beliefs were forged during the country’s military dictatorship. Following Brazil’s 1962 coup d’état, Dilma was active in Vanguarda Armada Revolucionária Palmares and Comando de Libertação Nacional, two far-left guerrilla organisations. On account of her involvement, Dilma served almost three years in the so-called Damsel Tower prison in São Paulo, where she survived twenty-two days of severe torture. Hardly the passive stereotype of a nurturing mother, Dilma has shown herself to be authoritative and independent.

Dilma’s presidency may symbolise the beginning of an era in which women play a much more active role governing Brazil.

Dilma’s victory will likely change the public perception of the role of women in Brazillian society. Her cabinet boasts a record proportion of female ministers: women oversee nine of Brazil’s 37 ministries. Among her reforms, Dilma hopes to incentivise women to join the labour force. These policies seem to be motivated by Dilma’s stated belief that society’s perception of women is fundamentally distorted. Two months after taking office, she remarked in an interview, “It is funny how we women are expected to be fragile. When a woman takes over a high position, she is regarded as being out of her normal role. I think that from now on, this will be seen as a natural, normal thing”.

Dilma’s presidency may symbolise the beginning of an era in which women play a much more active role governing Brazil. Her emphasis on equal opportunities adds a new dimension to Lula’s socialist creed, “A Brazil for Everyone”. Whether Dilma can implement the legal and economic reforms necessary to secure Brazil’s future prosperity remains yet to be seen. Nevertheless, her election strikes a blow to political culture in Brazil that for too long has placed limitations on the role of women in politics.

Photo by Gene Hunt via Flickr.

ECONOMISTS celebrate division of labor and specialisation as classical linchpins of market efficiency. However, the latest National Health Service (NHS) reforms, proposed by Tory Health Secretary Andrew Lansley, would remove both features from Britain’s national health care service. The Health and Social Care Bill, introduced in Parliament in January, requires that doctors subsume the role of accountants in the name of fiscal discipline, with the aim of slashing management costs in the healthcare industry by 45% over the next four years. If passed, the act would remove an entire tier of healthcare administration by shifting the onus of purchasing NHS patient services from primary care trusts (PCTs) to GPs. The proposed reconstruction of the NHS architecture would have considerable implications for Britain’s health system. Opponents fear that the quality of service provided by GPs to their patients could decrease as doctors struggle to adapt to their new commissioning role, and believe that the bill’s goals could be achieved using less extreme measures. Advocates argue that taking this hatchet to the NHS bureaucracy will reduce costs and enhance the healthcare efficiency and efficacy. Regardless, the reforms will not succeed unless the government can convince the public that cutting bureaucracy does not require cutting patient care as well.

The government’s plans have thus far proved unpopular among medical practitioners, many of whom assert that they possess neither the time nor the expertise to manage finances without assistance. James Gubb, director of the Institute for the Study of Civil Society’s Health Unit, argues that “the risks of ripping up the current commissioning structure in its entirety in favour of new, inexperienced organisations… are unquantified and in all likelihood unacceptably high.” Chris Ham, chief executive of health policy think-tank The King’s Fund, describes the proposals as “a very powerful cocktail of policies that are being pursued all at the same time when the NHS budget is getting very tight.” The British Medical Association, the country’s largest professional association of doctors, sharply condemned the proposed privatisation of medical services in March, arguing that market forces are ill-suited to achieve outcomes specific to the medical profession, such as patient satisfaction and holistic medical care. Giving individual GPs the power to allocate NHS funds could ultimately neglect funding for less common ailments, such as mental illness.

Conversely, in 2006, the Audit Commission published a report that claimed that the bill will distribute resources more fairly. Then-chairman Sir Michael Lyons summarised the report by claiming that the changes “would enable trusts and PCTs to achieve better value for taxpayers’ money and contribute to consistent, reliably funded services for patients.” Prime Minister David Cameron, who was elected on the promise that he would cut funding to the NHS, claims that the bill contains few policies that have not been implemented successfully in times of crisis by previous governments. He also maintains that the bill has attracted the support of many professionals in the medical community, and notes that more than one hundred practices have volunteered for a pilot scheme.

The government is selling the policy as a “win-win-win” situation for all parties: the NHS, clinicians, and patients. However, at present, the public remains skeptical. In April, David Cameron begrudgingly embarked on a two month “listening exercise” to persuade stakeholders in the healthcare system that the proposed changes will serve their interests. To succeed, he must convince the nation that patients, first and foremost, stand to benefit from the health reforms. If he fails, Lansley, the central architect of the proposed changes, will likely be remembered not for his brave attempt to slice through red tape, but for the nimbus of controversy that surrounded his reforms.

]]>

Dambisa Moyo. Photo by canada.2020 via Flickr.

In 2009, Time named Dambisa Moyo, author of Dead Aid, among the world’s 100 most influential people. During Hilary term, Mark Longhurst spoke with her about her latest work. The interview below is an edited account of their conversation.

In your latest book, How The West Was Lost, you argue that while the West has lost its competitive edge, Europe and the United States have an opportunity to win it back. What choices must the West make to avoid economic decline?

I think education is first and foremost. All of the fundamental problems that the West faces – education, infrastructure, energy efficiency, and so on – are things that are structural in nature. They are long-term problems that have been eroding capital, labor and productivity over a long period of time. It will take a long time to remedy these things, but those are three examples of things that they could do starting tomorrow in a very credible way.

Your book argues that education, infrastructure and deficit financing are three important priorities. On which factor should the West first focus?

There’s no one thing. You can’t have highly educated people without infrastructure. You can’t pick one. It’s about a portfolio of things. People will need healthcare, people will need education, you have to fund national security. But there has been too much investment in things that are consumption-related. This is fundamentally the problem. They have to move the focus away from consumption goods towards more on investment.

Is the West worth saving, or is the world be better off with a geopolitical shift in power toward emerging economies?

No, absolutely not. No one should rest easy if there is any form of suffering anywhere in the world. The notion that we should just let the US go, or let Europe go, is clearly unfounded. My first book, Dead Aid, touched on exactly this point. It’s not acceptable to let the continent of a billion people go in the way that the world has.

Economists tend to rail against trade protectionism. In your book, you note that the United States and China levy manufacturing and agricultural tariffs and subsidies. What role do you believe protectionism will play in the next fifty years?

To be clear, I am absolutely a supporter of free trade and the movement of capital and labor. But we live in the real world. In the real world, we know that Western countries engage very aggressively in protectionist practices – things like agricultural subsidies to Africa, that lock out African goods. My book is not saying that protectionism is not a good idea. What I am saying is that it’s a nuclear option, and it’s certainly on the table given the fact that a place like the United States has 30 million people who are out of work in the manufacturing sector.

You speak about the political reform that needs to occur in the United States and Europe, if the West wants to win back what it has lost already. How will Western governments begin to initiate the process of political reform?

I’m not a political scientist, or a person who deals in politics. This is obviously very complicated, and in some sense, people may argue, intractable. We have to get past the politics and the cycles. Politics encourages policy-makers to focus on short-term agendas and to not deal with the long term. The more pressure that is brought to bear on developed countries, the greater the demand on these countries to sort out these structural problems.

]]>

Photo by Mark Longhurst.

FOR decades, the United States has heard a steady increase in calls from economists for the federal government to eliminate one of America’s most time-honored and recognised symbols: the penny. In 2006, Harvard economist and then-head of the Economic Council of Advisors Gregory Mankiw listed the action among the top ten priorities for policy makers in the United States. In 2008, popular magazine the New Yorker reignited the debate with a pithy piece which advocated an end to the penny era. Despite the popular debate, Congress is loathe to agree. Legislation to cease production of the penny was twice introduced to Congress in the past decade, but has always failed to make it out of the House.

Further north, in Canada, the movement seems to be gaining ground. In December 2010, the Canadian Senate Finance Committee recommended that the federal government cease production of the penny and remove the coin from circulation by 2012. A few days later, polling data from an Angus Reid online survey found that 55% of Canadians support legislation to drop the coin from circulation.

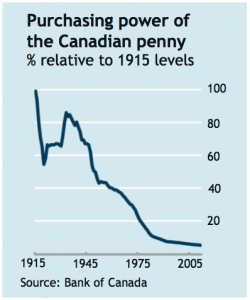

After a century of inflationary pressure, Canada’s penny has lost more than 95% of its purchasing power since 1900. The Canadian nickel now holds approximately the same purchasing power as a penny in 1972. Each penny costs the federal government 1.5 cents to produce, which means that the Canadian Mint manufactures pennies at a loss. The economic utility gained from the coin is marginal: pennies are rarely used by consumers to purchase items, and are not accepted by toll booths or vending machines. A 2007 study predicts that eliminating the penny could save the federal government approximately £83 million annually.

Unfortunately for penny opponents, Canadian finance minister Jim Flaherty released a statement in December that claimed “there are no plans to eliminate the penny.” Nevertheless, that a majority of Canadians are in favour of the measure suggests that, for better or for worse, the penny’s days are numbered.

]]>

Gold artifacts are more valuable than ancient mosaics. Photo by Ann Wuyts via Flickr.

SURROUNDED by the quiet streams and oak groves of the Strandja Mountains in south-west Bulgaria, the village of Rosenovo is home to 30 people who live bereft of standard luxuries, such as running water and paved roads. This is where my father was born. When he was a boy, he discovered the ruins of an ancient fortress on a hill nearby. Two millennia ago, a division of Roman soldiers controlled an area that stretched for 30 km to the city of Debeltum. I visited the site three years ago to accompany my father on a trip through his childhood memories. There, I found traces of plunder. I vividly remember standing over a gaping hole in the ground, almost two metres deep and four meters wide, full of tattered pieces of stone. Aggressive digging had revealed the outline of a small rectangular chapel with a rounded apse. I reached into the rubble and picked up a fragment of a painted mural about the size of my cupped hands that portrayed an important historical figure – perhaps an emperor or a saint. The mural had been shattered.

I experienced an art historian’s tragedy. Careful excavation might have revealed new insights into early Christianity in these lands. The historical foundations could have disclosed information about Roman defense strategies in this province. But this evidence has been all but lost, destroyed beyond recognition by organised human action.

Today, approximately 300,000 people engage in unregulated excavation for ancient Roman, Greek, and Thracian artifacts. The archeological gold rush began after the fall of the Communist regime in 1989. The early years of democracy and a free market in post-communist Bulgaria brought food shortages, hyperinflation, a defunct judicial system and rampant treasure hunting. Over the past two decades, thousands of years of history have been destroyed in Bulgaria. Only now is the government beginning to take up the challenge of regulating excavation and preserving Bulgaria’s ancient heritage.

The Vandals

Ratiaria is a city on the opposite end of Bulgaria from the Strandja Mountains, in the north-west. While this is the poorest area in Bulgaria, it is built upon one of the richest archaeological sites on the European continent. Unlike other cities from the Roman era, it stands buried exactly as it was abandoned in the fourth century AD. The richness of urban life in the Roman Empire has been preserved there for centuries; foundations of buildings, streets, household objects, burials and temples lie untouched beneath the surface. A man from Archar, the village nearest to Ratiaria, admits in an interview that he has unearthed and sold artifacts here. Many of his fellow villagers, for whom digging is one of the few available sources of income, supplement the meager earnings from their day-jobs with the proceeds generated from trading artifacts.

Archaeologist Krasimira Luka calls Ratiaria “the local Klondike.” Most locals use small tools, such as shovels of their bare hands, to search for pieces. Those with the means to do so use bulldozers and explosives to excavate larger antiques. In either case, information used to date the objects is inadvertently destroyed during the process. The dynamics of treasure hunting mean that only objects that yield significant profits – such as precious metals, luxury vessels, jewelry, statuaries, and stone reliefs – tend to survive this process of “natural selection”. Unmarketable artifacts are abandoned or destroyed. Many Bulgarian locals locals consider collecting samples of mortar and domestic wall paint a pointless exercise while valuable coins, jewelry pieces, and small statues lie untouched beneath the earth’s surface. For this reason, intangible, though archeologically valuable information, such as evidence relating to city-planning or specific architectural styles, is often completely lost. In Ratiaria, the economic incentives govern the politics of ancient art.

The Villains

The promise of greater profits persuades many diggers to export antiques to markets where they can fetch the highest price. On March 7th 1994, Svetozara Kirilova, a flight attendant on a Balkan Airlines flight from Sofia to New York was asked to forward a small suitcase to an individual in the United States. Suspicious of the contents, she opened the suitcase to discover what was later reported as “over 3000 silver, copper, and bronze Roman coins, plaques, fragments, earrings, bracelets and other valuables” valued at almost £45,000. By law, all of the artifacts belonged to the Bulgarian state, and a trial ensued accusing four people as the organisers of the illegal export. However, four years later, Kiril Ivanov, district prosecutor for Sofia City, discontinued the trial. In 2001, it was reported that the confiscated suitcase had disappeared; nobody could determine the location of the coins. In 2009, a newspaper reported that the documentation about the trial had disappeared. After a journalist requested access to the court records, it turned out they were no longer extant. In the absence of strong law enforcement, criminal networks of diggers and traders have evolved into a treasure-hunting mafia. The judicial system had failed to protect the “national” valuables; they were not more secure under its custody than they were as contraband to the United States.

Ministers can do little better. Stefan Danailov, then-Bulgarian Minister for Culture, sent an official letter to the auction house Christie’s in London asking them to stop the auction of a silver dish of either Roman or Byzantine origin. The artifact was illegally looted near the town of Pazardzhik in 1999, Danailov claimed, and it belonged to Bulgaria. Christie’s replied that the dish was exported from Bulgaria to the UK back in 1903, and was now legally part of the Stanford Place Collection. Even when a man from Pazardzhik stated he was the one who found the plate with his metal detector, the auction house did not consider returning the object. Yet Christie’s auction house raises a fair objection to the minister’s claim. Many Bulgarian artifacts belong to ancient cultures whose heritage is spread over the territories of different nations today. Roman antiques, in particular, are mobile and international by nature; from coins to column capitals, their artifacts present a unified style that was used by the empire authorities to export their influence to the most distant provinces. Why Bulgarian state ownership? Why not Italian or (as Christie’s wanted) private ownership?

The Hero?

Admittedly, some collectors are making a considerable effort towards preserving ancient artifacts for Bulgaria. The figure of the philanthropist-collector is epitomised by Vasil Bojkov, a Bulgarian businessman with a fondness for Thracian treasures. Bojkov has registered his collection with the Bulgarian Museum of Natural History; he is one of only 200 collectors to comply with an ultimatum that requires such officiation. He is also preparing an exhibition of rare silver and gold Thracian rhytons: royal drinking vessels of cast metal sculpted in the shape of animal heads. In a public statement, he said: “The Cultural Heritage Law and its enforcement by the state administration leave Bulgaria outside of the European museum network. It must be known that the collector is not a treasure hunter, but rather a guardian of the national heritage.”

In some cases, artifacts fair better in private collections like Bojkov’s than in museums. Typically, private collectors have greater access to suitable funding for research and conservation than museum curators. A museum internship in a small Bulgarian town led me to a leaky basement where stacks of historic paintings from the Socialist era were slowly decaying from the effects of mould damage. Limited state funding prevented management from purchasing proper facilities to preserve these works. For this reason, private collectors tend to resist complying with orders made by the government to confer what they believe is their rightful property.

While Bojkov may not be a treasure-hunter, chances are that his treasured rhytons were acquired illegally. In April 2009, Bulgaria passed the Cultural Heritage Law, which requires any sale of cultural property purchased legally to be registered with the state, and offered first to the Culture Ministry for purchase by the national collections. If the rhytons were purchased legally, then any sale that Bojkov made would have been registered by the state and likely (given the objects’ cultural worth) seized by the government. The law as it stands is weaker than its original version, which mandated that collectors provide documentation for all objects in their collection that possessed significant cultural value to Bulgaria, regardless of whether the items were involved in a transaction. This law was criticised by archeologists, who claimed the mandate would force otherwise honest collectors to produce fraudulent documentation, and by collectors, who considered the law too intrusive. The constitutional court agreed with collectors and declared the provision unconstitutional. Consequently, the remaining statute provides collectors with an incentive to hoard their pieces, lest the government confiscate their artifacts during a sale.

Bulgaria is attempting to negotiate a compromise between a model of total government control inherited from Socialist era and the market approach pioneered by capitalist economies. Already, the government can point to some modest success. Last year, police brought a record number of legal actions against treasure hunters. Private homes were searched and hundreds of artifacts were confiscated. However, progress is inhibited by the legal onus placed on the government to demonstrate its right to ownership. The process of staking a claim remains cumbersome. The government must establish not only that Bulgaria is the most probable place of origin for a certain object, but also produce specific evidence of when and where the object was unearthed. As demonstrated by the situation in Ratiaria, such records are often impossible to obtain.

Bulgaria’s relics, both above and below the earth’s surface, deserve protection. As long as the antiques trade remains lucrative, market demand will continue to provide a driving force for illegal excavation in the future. In response, the Bulgarian government should prohibit archeologically destructive practices and prosecute offenders. In addition, using a delicate cocktail of market regulation and state controls, the government must work with collectors to protect Bulgaria’s existing antiques. Only then will academics be able to piece together the narrative of a country whose artifacts trace more than 7000 years of history.

]]>