Emblem of the National Security Agency, which has Cyber Defense Division. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

At the heart of John Bassett’s talk on networking operations and cyber security was the suggestion that web-based commercial and security strategy is no more than simple evolution – the 21st century equivalent of a typewriter. According to Bassett, the Internet has had a quantitative, rather than qualitative, impact on business, crime, and warfare. This should be reassuring, and to those military strategists and IT specialists who agree, it is. Network defence is the 21st century version of the electronic security preoccupation of the Cold War, network exploitation for enforcement or espionage purposes is the equivalent of human intelligence, and similar likenesses can be drawn for the other two categories of network operations – attack and infiltration. Likewise, what Bassett calls ‘the vector’ of a cyber attack is still human and continues to be the weakest link.

So why are governments and academics worried, criminals delighted, and businessmen pensive about potential cyber attack? For starters, because we live in a global economy where computer parts and software packages come from all over the world, the high risk of infiltration is mind-boggling. The economic implications of a country like the United States or United Kingdom deciding, for security reasons, to begin domestic sourcing would shock the current global supply system. Although Bassett doesn’t suggest that supply-chain attribution issues will cause anxious governments to act in this manner, he does imply that the heightened level of insecurity that politicians and military planners feel in their respective networks is justified.

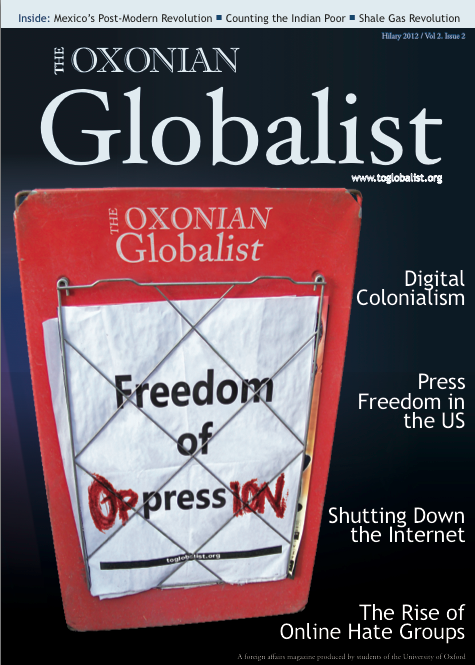

But what does this mean for individual privacy rights or the Freedom of Information Act that news outlets rely upon? What kind of government lash back from cyber escapades like Wikileaks should be tolerated by the public? According to Bassett, these questions emerge as part of the qualitative shift that the Internet has precipitated. The changing nature of information distribution may require governments to bring about a shift in the way they view classified information, though members of every international intelligence community might like to see secrecy buffed up. Bassett also pointed out that increased secrecy comes at a cost to information sharing with a government. This is particularly critical at a time when the number one threat to the United Kingdom – terrorism – requires pooling of information between government agencies and allied nations in order to combat effectively.

Internal operations were not Bassett’s primary concern, nor were state-funded cyber attacks launched against other states, though he admits freely that others may be more alarmed by the potential strategic advantage of full-fledged cyber warfare. To illustrate his opinion, Bassett points to the limitations of the Stuxnet virus’s ability to inflict severe damage on the Iranian nuclear program. Bassett reminds that sophisticated cyber weapons are intellectual capital intensive to produce, can easily become outdated as systems change, and once used can never be used again. Building a stockpile of nuclear weapons, each of which required a Los Alamos sized effort to generate, had to be uniquely designed, and would degrade in months. The implication of this assessment for cyber war is that countries with sophisticated cyber capabilities would incur substantial costs (and uncertain benefits) in an attack against an equally capable state without the aid of physical weaponry. However, in a conflict in which the two sides are unevenly matched, cost-efficient damage is more easily achieved. For example, both Georgian (in 2008) and Estonian (in 2007) network systems were incapacitated by attacks, and had to be resuscitated by foreign experts.

However, Bassett surmises that the largest cyber threats are those of lower and middle level cyber crime directed toward the commercial sector, and David Cameron seems to agree. Both men send the same message: protecting John Lewis is just as important as guarding the Ministry of Defence’s systems, which is why the UK government has listed cyber security as the second largest threat to the nation, and intends to devote substantial resources to cyber defence. Given the sheer number and importance of online commercial interactions, the business community and its customers stand to loose the most from cyber crime, and paradoxically are the least well protected. The government’s role and responsibility in protecting business and consumers is tricky, especially following the accusations of ‘pandering’ that followed the financial crisis. Nevertheless, Bassett suggests and Cameron seems to agree that the government’s role in establishing the conditions and information base for the defence of public network systems, and to a limited extent for the private sector, are well worth the trouble – even with a tight budget.