FOR decades, the United States has heard a steady increase in calls from economists for the federal government to eliminate one of America’s most time-honored and recognised symbols: the penny. In 2006, Harvard economist and then-head of the Economic Council of Advisors Gregory Mankiw listed the action among the top ten priorities for policy makers in the United States. In 2008, popular magazine the New Yorker reignited the debate with a pithy piece which advocated an end to the penny era. Despite the popular debate, Congress is loathe to agree. Legislation to cease production of the penny was twice introduced to Congress in the past decade, but has always failed to make it out of the House.

Further north, in Canada, the movement seems to be gaining ground. In December 2010, the Canadian Senate Finance Committee recommended that the federal government cease production of the penny and remove the coin from circulation by 2012. A few days later, polling data from an Angus Reid online survey found that 55% of Canadians support legislation to drop the coin from circulation.

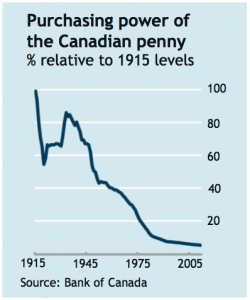

After a century of inflationary pressure, Canada’s penny has lost more than 95% of its purchasing power since 1900. The Canadian nickel now holds approximately the same purchasing power as a penny in 1972. Each penny costs the federal government 1.5 cents to produce, which means that the Canadian Mint manufactures pennies at a loss. The economic utility gained from the coin is marginal: pennies are rarely used by consumers to purchase items, and are not accepted by toll booths or vending machines. A 2007 study predicts that eliminating the penny could save the federal government approximately £83 million annually.

Unfortunately for penny opponents, Canadian finance minister Jim Flaherty released a statement in December that claimed “there are no plans to eliminate the penny.” Nevertheless, that a majority of Canadians are in favour of the measure suggests that, for better or for worse, the penny’s days are numbered.