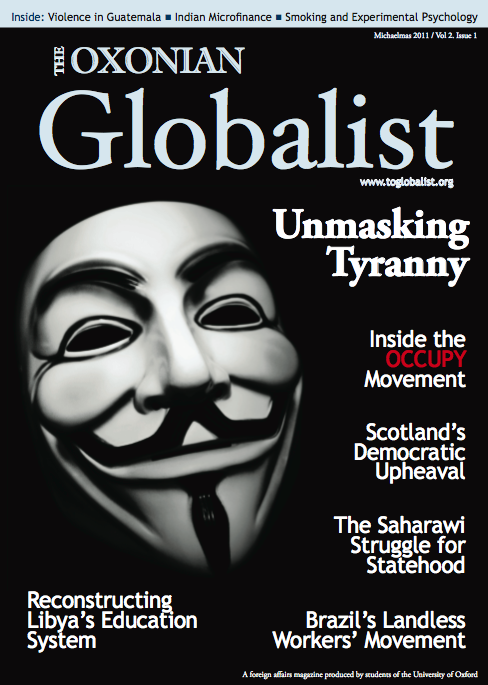

Despite its manicured lawns and golden walls, does Oxford really teach students how to think for themselves? Photo by Natasha Rees.

In October of last year, I walked down St. Giles, past Merton and Trinity and Blackwells and centenarian pubs, to the Radcliffe Camera, and sometimes I would walk just a little bit faster when the sun peeked out behind the clouds and the walls at Oxford began to glow yellow. Being at such a place is thrilling because it tells you that if you achieve a certain standard, you will catch that ever-floating-just-beyond-reach winged golden snitch: “success”. Trinity courtyard told me with its manicured lawns, its wrought iron gates, gilded crest, and high arch, that when I walked out of a tutorial victorious and through its path that I, a lowly American from quaker-simple Swarthmore, had made it.

I have come back to Swarthmore, a highly ranked liberal arts college just outside Philadelphia, and the gilt, pomp and circumstance are gone. The manicured lawns remain, and so I sat on one in a sturdy wooden Adirondack chair, the traditional purview of New England seaside homes, while contemplating where I had been and where I was now. When I was at Oxford, I studied PPE –primarily Kant and Post-Kantian philosophy, and international relations. In response to the requirement of two essays a week, I had organised a neat mechanism of writing one of these papers: get reading. If philosophy, skip the primary reading (who can master The Critique of Pure Reason by reading Kant himself?) and deal with the Routledge Guide, Cambridge Companion, or Kant Dictionary. Read secondary literature furiously. Identify one argument that appears to have logical inconsistency, ambiguity, or flaw. Critique. Write essay. Go to tutorial. Look at essay – 70 – win! Go to dinner. Drink. Sleep. Repeat.

At Swarthmore, I am enrolled in the Honors program, which is based on the Oxford tutorial system, with four seminars and final exams at the end of the course. I do not get as much attention in class: while I still have class only two times a week (I am taking two Honors seminars) it is shared not with one other student, but with an average of eight. I do not write as much – students either write short, ungraded papers every week, and just a handful of students write longer papers.

Yet I don’t much mind. Because of the fewer papers and larger groups, Swarthmore Honors seminars emphasise group discussion, free inquiry, and original thought over pedantic critiques. The good students know these critiques, but the Swarthmore professors who run Honors seminars would tell them that “that’s not really the point”. Easy meaning, like easy money, doesn’t come cheap. To say something both sound and original requires applying the text to real-world examples, making strides away from the text itself, and fighting with fellow students across the seminar table, rather than writing a paper alone, hearing critiques, and simply returning to the Bodleian to smack one’s head against the books for another few hours. Students are encouraged to leave their literature- crutch behind, and walk freely on the map of the text, forging their own paths along the way.

This, admittedly, has not been an easy transition. I leave my Adirondack chair and the well-manicured, sloping lawn to return to the library, stopping on the way to examine what is likely the most famous spot at Swarthmore. It is no Bodleian, but it was featured in an “Oprah Book Club” book, which among certain suburban, TV-watching circles is just as good. In front of me is a plaque from 1921, grouted into the stone exterior of our central building. It reads, “Use thy freedom well” and is the source of the title of Jonathan Franzen’s American epic novel Freedom, first published when I arrived at Oxford last year. Franzen’s book captures the theme of the American tendency towards destructive excess, but seeing as I know the spot personally, I like to look at it sometimes and remind myself that we are all free to think as we will, to be brave enough not to be a mouthpiece for the books of giants but to stand, as Newton did, on the shoulders of giants – or, at least, to try to. Despite the gilt and shapely lawns and glowing walls and cobbled stone of Oxford colleges, those who walk among them must find, as I did not, their own meanings anew.

Now, I am off to the library.