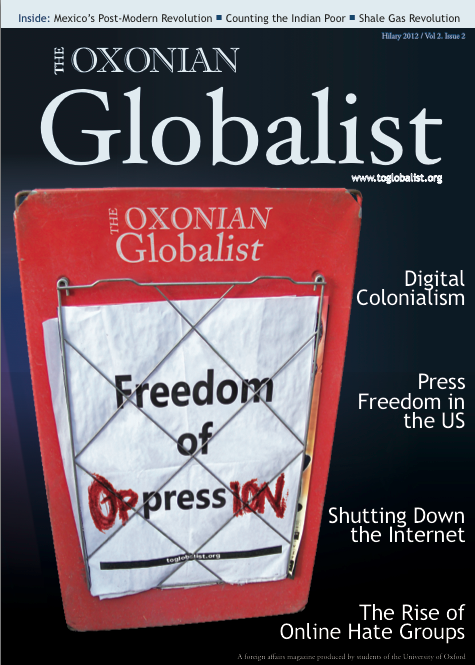

Mamun received treatment for diarrhoea through a health insurance scheme run by a local NGO. Photo by Jemima Peppel-Srebrny.

A big fly, buzzing and circling around her head, settles in the corner of her eye. Another, right next to her mouth. No one seems to care, or have the energy to shoo them away. Mita is seven years old, has been unable to go to the toilet for five days, and has been camping in the hallway of a public hospital in Mymensingh, Bangladesh, with her parents for the last three. She was responsive yesterday, but today, spread across her mother’s lap, her eyes are half-closed and she does not seem to be aware of the group of people that has gathered around her to hear her mother tell her story.

The Mymensingh hospital has twice as many patients than beds, plus seemingly at least three “attendants” per patient, family members who eat, sleep and live on and around the bed or mat or floor space of the ill. The hot air is reeking; the floor is covered in dirt, blood and vomit; excrement is running down the building’s outside walls and forming pools in the courtyard. To get treatment, you have to come to the hospital to register, and then stay there to wait for your turn to receive treatment or surgery. Depending on your willingness and ability to pay, this can take hours, or weeks, regardless of the urgency of your situation.

Mita’s parents cannot afford to pay to skip the queue, having spent their savings on transportation to get their daughter to the hospital and getting themselves deeper and deeper into trouble with every day they stay not earning money. They do not know when their daughter will receive treatment. The hospitals’ doctors are absent or work a fraction of the time they should, and spend their afternoons working in profitable private clinics instead. To make matters worse, demand for drugs outstrips supply by as much as five times in some instances, and many more days of hospitalisation than would normally be needed are required due to reinfection and the spread of infections. “Ami kushi, ami dead” – “I am happy, then I am dead” is our driver’s opinion about hospitals, which he declares in his characteristic Banglish as we return to the car.

“Frustration, hopelessness and anger are outsiders’ usual reactions to seeing facilities like this”, a microfinance and insurance expert from a local NGO says. Gut-wrenching sadness and outrage are two to add to the list. Mita’s slow and unnecessary death on the hospital floor exposes the continuing lamentable shortfalls of governmental and non-governmental development efforts.

Poor healthcare is, predominantly, a problem for the poor in Bangladesh. There are persistent, gaping inequities in healthcare provision across social groups and geographic regions. Coverage of crucial healthcare services such as skilled birth attendance remains very limited. The better off can usually afford to go to private clinics; serene, hygienic castles of dreams in white for many of those stuck at the overcrowded public hospitals. The poor tend to, if at all, receive low-quality health services, and are overall of worse health than the better off. Among street dwellers, for example, limited access to clean water and sanitation, bad nutrition, exposure to sexual violence and police brutality together with social ostracisation mean that they suffer from numerous untreated health problems, including vitamin deficiencies, infections, sexually transmitted diseases, fractures and damage to internal organs; similar holds true for rickshaw drivers and their families. All of this is in spite of the fact that the Bangladeshi constitution promises each of its citizens the right to free primary health care.

Over the past decades, various NGOs have stepped in to attempt to fill the gap created by the combined failure of government and markets. Through micro health insurance schemes, they have been trying to improve the poor’s access to affordable healthcare services and protect them from the financial implications of catastrophic health shocks. Initially hailed as the “next big thing” in microfinance, such insurance schemes have, however, rarely done well, most marred by structural shortfalls of income from premium collection over costs for benefit provision when government and donor subsidies run out. They have further been hampered by their small scale, which limits their ability to achieve risk diversification and hence exposes them to large fluctuations in their expenses. Moreover, a somewhat self-defeating exclusive focus on the poor – who have lower ability to pay for health insurance and tend to be of worse health – frequently undermines these schemes’ cost recovery and also prohibits the subsidisation of poorer people’s health costs by the richer, which is fundamental to most insurance schemes in mature economies.

Fortunately, however, there is some good news. For one thing, Bangladesh has made astonishing progress in bringing down child mortality, by nearly two thirds over the past 20 years to 48 per 1,000 live births, beating India by far. It has also achieved nearly complete immunization against DPT (95%) and measles (94%) of its 12- to 23-month olds, with India (72%/74%) again far behind. Bangladesh’s progress has prompted Amartya Sen to laud Bangladesh for achieving “so much so quickly” in terms of human development and for doing much better than India despite its substantially lower per capita income. At the same time, the academic and development communities are increasingly coming to realise the huge implications that falling ill can carry for the poor, in keeping them poor or pushing them further into poverty, and are dedicating time and resources towards improving access, affordability and quality of healthcare, in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

Lastly, charities in Bangladesh are thinking again about micro health insurance, and are coming up with novel approaches to tackling the many challenges involved in setting up and running such schemes. One interesting idea has been to link the insurance scheme to a catastrophe fund that gives out long-term loans at low interest rates to members facing catastrophic healthcare expenditures. To ensure effective risk protection, what “catastrophic” means can be defined relative to the income of the affected household. The fund can be financed through an endowment, the return on which could make up for some of the shortfall in loan recovery, through other NGO activity, or through government and donor subsidies. At the same time, commercial reinsurance could help the insurer stabilise its expenses and avoid insolvency in “bad” years. Broadening the insurance pool to include formal, better off individuals as well as informal sector workers could also help to diversify risk and achieve scale and financial sustainability.

Realistically, NGO-driven micro health insurance is unlikely to be a panacea or cure-all. For achieving universal health coverage in Bangladesh, a concerted effort and the commitment of the government are indispensable. Nonetheless, government and development organisations’ efforts to improve health, a creeping realisation of the importance of health for all other pieces of the puzzle of development and NGO’s renewed efforts in devising sustainable, effective health insurance schemes mean that there is reason for hope – hope, at least, that what happened to Mita will happen less often in the future.