Mass Destruction: Part of the Japanese coastline after the earthquake and tsunami. Photo by Kordian via Flickr.

LAST year was the costliest on record for natural disasters. The floods in Australia in January, a 6.3 magnitude earthquake in New Zealand in February, Japan’s earthquake and tsunami in March, and a string of tornadoes in the southern United States in April resulted in the first half of 2011 seeing $265 billion in economic losses. These first six months beat the previous record of $220 billion for the whole of 2005. There has also been an increase in the number of incidents; more events were observed during 2011 than during any year before 2005 in recorded history.

If the upward trend continues in 2012, will the insurance industry be able to cope? Rapid urbanization means risks are more concentrated in certain areas, so if a disaster hits a major city, insurance companies will scramble to cover losses. The global financial crisis also took a big bite out of the insurance industry; since investment portfolios have performed badly, insurers have less cash available to cover the next big event.

Patrick McSharry, an academic expert in wind modelling and director of the Oxford Centre for Catastrophe Risk Financing, describes his work in the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment with the global insurance industry: “Uncertainty is really feared by insurance companies. They wouldn’t have a business without uncertainty, but now they struggle to measure it.”

Catastrophic events that do not happen often, such as major hurricanes and earthquakes, are difficult to predict because most of our risk estimates are based on historical records. For example, Japan’s 2011 earthquake with a magnitude of 9.0 was one of the five most powerful earthquakes ever recorded – but then modern-quality record-keeping only began around 1900.

Making Models

“Whereas we have a good idea of the risk of car accidents or house fires, it is very difficult to get an accurate estimate for infrequent events for which we have very little real data,” explains Raveem Ismail, an independent analyst at Trinakria Limited. “Insurance companies must combine historical records with cutting- edge research on natural phenomena from physics and meteorology, plus human behaviour for perils such as terrorism.” Even then, no one predicted many of the disaster events in 2011, or that they would all need insurance in rapid succession.

As a result, most catastrophic risks are under-priced by the insurance industry. In some ways, the global insurance industry operates much like a local marketplace. Syndicates, brokers, and insurance companies negotiate over prices, each relying on different private estimates, and there is a heavy temptation to lower prices to beat competitors. In the case of infrequent events, it is much easier to under-price for a long time. If insurance for a “100-year flood” is sold as a “200-year flood” at half the estimated price, it is possible no one would notice in this lifetime. On the other hand, if that event does happen, then the insurance company hasn’t collected enough premiums to cover the balance. One big event can wipe out many years of premiums.

There is also a social cost to under- pricing. When disaster strikes, governments usually assist with emergency recovery and reconstruction. If insurance companies cannot cover their claims, a bigger burden falls on government budgets and ultimately on taxpayers for years to come. Insurance companies are truly “too big to fail” when it comes to coping with the worst disasters. Yet if the government commits to bailing out private insurance companies, the industry faces a moral hazard problem – the temptation to increase short-term profits by holding insufficient liquidity. Facing increasing disaster risk, the EU has proposed stiffer regulations with the “Solvency II” directive, which would increase capital requirements for insurance companies by 2014. McSharry warns, “Everyone agrees that Solvency II is a good idea in principle. The real struggle is bringing together enough staff to get models ready in time.”

Numerous efforts are underway to improve catastrophe risk modelling. Most insurance companies have their own proprietary models, but if no one wants to share these trade secrets, it is difficult for anyone to understand the big picture of global risk. When two different models disagree, underwriters cannot easily dissect them, so it is more difficult to make business decisions based on model outputs.

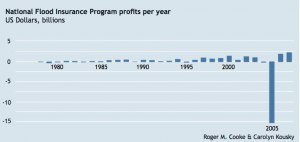

National Flood Insurance Program premiums minus losses per year, where Hurricane Katrina in 2005 dwarfs insurance profits from the previous 30 years

If the Price is Right…

Academic institutions, such as the Oxford Centre for Catastrophe Risk Financing, are helping coordinate collaborative modelling between finance, technology, government, and researchers. The Global Earthquake Model (GEM) was set up in 2009 as to allow open access modelling including both financial and socio-economic effects such as health, migration, and employment. In the future, GEM, like the Global Risk Register that launched in June 2011, will even allow individuals to input their own information to understand their personal risks. “The more people are aware of possible risks and impacts, the more they can prepare. Uncertainty shouldn’t be seen as a weakness. Any honest model, like a doctor before an operation, should tell you about the risks and believe individuals can handle that information,” says McSharry.

But in developing countries, private insurance markets are often non-existent or informal, making the poor even more vulnerable. “Being poor is not just about having a low income – it’s about having a very risky income,” says Daniel Clarke, micro-insurance consultant and lecturer in Actuarial Science at the University of Oxford, who has worked in numerous developing countries. “If a harvest was bad in India, it used to be that farmers waited for assistance for up to a year because it took so long to reallocate government budgets toward the emergency, and this happened almost every year.” In the case of a major disaster, or even routine bad weather, it is costly for insurance companies to visit each person to assess damages, and those costs trans- late into higher prices that most people cannot afford.

Recent innovations in index insurance help to make payouts faster and more accurate. Index insurance pays everyone in an affected region, regard- less of individual losses. Now with an index insurance program pioneered by the World Bank, the Indian government pays insurance companies upfront to cover 30 million farmers, who can receive payouts almost immediately in case of bad weather, meaning they can invest in better seeds, fertilizer, and supplies for the next year.

“Turkey’s national earthquake insurance program has also been very successful,” adds Clarke. The government spends a lot of money educating people, but they invest in their own insurance, and it has paid off: “The trick is for insurance companies to design indexes that actually pay out when the event hits. Offering good insurance at the right price is still the biggest challenge in the future.”