Access denied. Published scientific research has traditionally only been accessible through costly subscriptions and individual purchasing schemes. Photo by jmv via Flickr.

Articles vetted by peers and published in academic journals have long been the currency of scientists, serving as the medium through which research findings are shared with the wider world. Access to these articles, however, has never been free. On the contrary, affiliation with a university that purchased expensive journal subscription packages was, until recently, a near requisite for gaining access to the latest scientific discoveries. The only alternative was to buy individual articles from publishers on a one-off basis, usually for a fee of between US$15 and US$30 (£10 and £18) each.

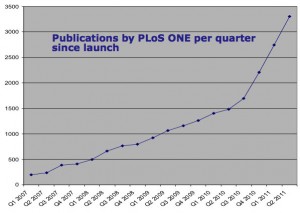

The last decade, though, has witnessed remarkable change. The most recent push from many researchers, librarians, university presses, and even some publishing houses has been the provision of free, open access to published research. Leading the revolution, open-access publishers like BioMed Central and the Public Library of Science (PLoS) have actively defied the old guard of traditional academic publishing houses, making all articles in their journals freely accessible on the web. Submissions to such journals have been rising almost exponentially; just five years since its launch in 2006, PLoS ONE published almost 14,000 articles last year, making it the largest peer-reviewed academic journal in the world.

PLoS ONE published almost 14,000 articles last year, making it the largest peer-reviewed academic journal in the world.

An Open Debate

Such changes in the publishing landscape have not been without controversy. Major scientific publishing houses like Elsevier, with revenues of US$3.2 billion (£2 billion) in 2010, assert that they add substantial value throughout the publication process. Organising the peer-review system, providing editing assistance, and marketing the journals in which academics publish are among the services they claim must be covered. Indeed, the costs of publication are by no means zero; open-access publishers cover such costs by charging researchers – up to US$5,000 (£3,100) in the case of Nature Communications – to publish an article.

Proponents of open science, however, are not convinced. They argue that journal publishers are high-margin businesses which exploit researchers as unpaid reviewers then charge exorbitant rates for access to new research findings. Elsevier’s 37% profit margin last year, they say, is glowing evidence of this injustice. Many of the scientists themselves believe that restricted access is actively hindering faster progress in the discipline; since January, over 11,000 researchers have joined a web-based boycott of Elsevier. “No matter how much value peer review adds” says open science activist Michael Eisen, founder of PLoS, “it cannot make up for the myriad ways in which traditional scientific publishing retards scientific progress.”

Although the movement for open access to published research is growing, practical concerns abound. For one, academic promotion and tenure are still largely contingent on finding one’s name in print in the most prestigious journals a field has to offer. The majority of these are still run by for-profit publishing houses requiring pricey subscriptions. Service to journals in the form of editing or reviewing is also valued highly by universities when looking to promote. Thus refusing to provide such services to closed journals can become a difficult, perhaps career-limiting decision for a young scientist.

Legislative Action

The debate over access has not stopped at online advocacy forums. In December 2011, two members of the US Congress introduced a piece of legislation called the Research Works Act. The bill proposed barring federal agencies from doing anything that would result in the public sharing of research published in private journals. If passed, such a law would have spelled the end of policies like the US National Institute of Health’s (NIH) public access requirement, which mandates that the results of research conducted with public funds be made openly available on its database within a year of publication. Although the Research Works Act was initially backed by a number of large publishing houses, Elsevier formally withdrew its support in late February after intense criticism from the academic community. The bill’s two congressional sponsors have also recently promised not to pursue further legislative action.

An opposing piece of legislation, dubbed the Public Access Act, was introduced in February. Its goal is to expand the public access mandate of the NIH to even more governmental agencies, and to change the time limit for online posting from one year to six months. Non-governmental bodies have begun to take notice as well. In April, the UK-based Wellcome Trust, responsible for funding £650 million (US$1 billion) of scientific research annually, announced intentions to sanction grant recipients who do not make their research findings openly available. The trust has also introduced plans to create a new high-end open-access journal, called eLife, meant to compete directly with prestigious publications like Nature and Science.

Access Granted

In an election year such as this, the Public Access Act is unlikely to make much progress. But the recent legislative back and forth highlights the success the open science movement is having in pushing issues of access into the highest spheres of public policy-making. Publishing companies are no doubt feeling the pressure. Although academic tradition still rests heavily on their side, open science activists have gathered serious momentum.

If nothing else, the movement has been successful in shining a critical light onto the traditional publishing process that has existed, with little change, since the 17th century. For the most part, scientists have been more than thankful for this. Cash-strapped libraries have already begun to drop subscriptions to expensive journals, and open publishers are becoming popular choices for the scientific community. As a result, publishing houses are beginning to prepare for a future that doesn’t exclude the vast majority of individuals from accessing research. For those with trust in the process of scientific inquiry, one thing is for sure. After rigorous testing and a bit of experimentation, the strongest model will ultimately rise to the top.