Censorship and Revolution: Memory as Prison

Few films spur the level of ferocious historical, political, and philosophical debate elicited by the 1966 Italian “shockumentary” Africa Addio. Africa Addio depicts scenes of brutal violence among “primitive” peoples, both real and staged, under the pretense of legitimate ethnographic study. Preposterous as this may sound, the film anchors itself in conventional assumptions of its time. Passing itself off as a dispassionate examination of postcolonial African malaise, the film begins by showing the viewer an independence ceremony in an unnamed African country. What follows is little else than a morbid catalogue of massacres and tortures; this is the real Africa, shouts the film’s notorious tagline, where “black is beautiful, black is ugly, black is brutal!”

Unfortunately, this sort of patronizing discourse remains ingrained in the minds of many Westerners. Western views of Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion stand as a testament to the terrible consequences of this mentality. Framed by both sides of the conflict as a struggle for peace and security, it led to some of the worst human rights abuses of the twentieth century. Although it set the stage for Kenya’s independence in 1963, the conflict divided native Kenyans and left thousands killed, maimed and traumatized. However, many war crimes perpetrated during the conflict were neither resolved nor avenged. The conflict also never underwent a thorough examination, leaving harrowing memories to fester in the minds of survivors for years to come.

Instead of Africans acquiring greater agency by way of constitutional change, Kenya’s European settlers continued to dominate the country economically and politically well into the 1950s. In the 1950s rural violence escalated and eventually consolidated into the Mau Mau movement. Most Mau Mau fighters belonged to the impoverished Kikuyu ethnic group. The Mau Mau then launched a redoubtable guerrilla campaign that terrorized their opponents, and a ruthless British counterinsurgency campaign ensued. Entire communities soon found themselves besieged by indiscriminate search-and-arrest tactics that often resulted in death, imprisonment, and torture.

Only time can wash away the scars of civil war. Nevertheless, the victims of the Mau Mau conflict continue to seek peace. Viktor Frankl, a world-renowned psychologist and Holocaust survivor, proposed that the last –and most fundamental- of the human freedoms is the ability “to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances”. Choosing one’s own attitude is first and foremost a question of narrative; therein lies the essence of dignity.

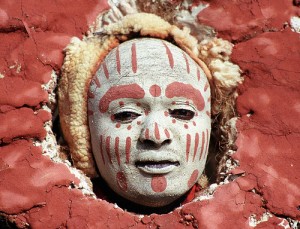

Kenyans siding with the Mau Mau could not express their own narrative. Part of the problem laid with the Mau Mau themselves. Firstly, the Mau Mau did not actively seek diplomatic contacts outside of Kenya, allowing the British to dominate the conflict’s news coverage and later its historiography. For this reason, the outside world perceived the Mau Mau as atavistic terrorists, driven mad with bloodlust. In the eyes of the West, the Mau Mau were less a revolutionary movement to be understood and negotiated with than a disease to be eradicated. The ruthlessness of Mau Mau guerilla tactics compounded this problem by providing more than enough fuel for the British government’s Manichean discourse, in which they described Mau Mau members torturing and mutilating civilians.

In the eyes of most people, no cause can justify such ghastly violence. How could the British stand idly by as Africans subjected each other to the worst excesses of human cruelty? The truth, however, was much more complicated. Both sides carried out acts of unspeakable violence; civilians of all races suffered immensely until the conflict’s termination in 1960. It would be just as obscene to rank the suffering of these groups as to suggest that the carnage sown by the Mau Mau invalidates its supporters’ wish for a more even-handed representation in history. Their wish remained ungratified until 2010 when Kenya finally recognized members of the Mau Mau as freedom fighters who sacrificed their lives for an independent Kenya. Prior to this, the Kenyan government refused to acknowledge the Mau Mau’s contribution to independence. Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s “founding father”, began this policy of forgetfulness. The Mau Mau were, by his account, a disease “which had been eradicated, and must never be remembered again”.

One can understand Kenyatta’s attitude better by considering Kenya at the time of his election. Kenyatta’s goal as leader was, first and foremost, to prevent Kenya from succumbing to civil unrest. In a speech made less than a year after independence, Kenyatta implored his countrymen to “never refer to the past,” so that Kenyans might unite in all their “utterances and activities, in concern for the reconstruction of our country and the vitality of Kenya’s future”.

At that time, Kenya was in a precarious situation. Former Mau Mau lived next door to loyalist Kenyans who, in some cases, had been personally involved in the conflict. Those Kenyans who had been loyal to the British reaped the benefits, living in comparative luxury next to their former adversaries. Furthermore, many British remained in Kenya after independence, where they continued to lead privileged lives.Demands for vengeance abounded, and only Kenyatta, having once faced imprisonment for anticolonial activities, possessed the moral legitimacy to contain the anger.

Kenyatta’s decision to remain a political moderate posed another problem for the construction of a Mau Mau historiography. Even during the conflict, Kenyatta presented himself in opposition to the Mau Mau movement, deeming their guerilla tactics objectionable. After independence, Kenyatta sought to marginalize Mau Mau sympathizers. For instance, when Mau Mau veterans demanded that the Kenyan government return the land that the British had confiscated from them during the conflict, Kenyatta refused, telling them “nothing is free”. Later, Kenyatta would go on to criticize calls for compensation from former Mau Mau as illegitimate. “We are determined to have independence in peace, and we shall not allow hooligans to rule Kenya,” proclaimed Kenyatta while addressing a crowd in the town of Kiambu. Those ex-Mau Mau who continued to speak out were eventually imprisoned.

Kenyatta wanted more than just the creation of a firm Kenyan national identity. In order to win their political and economic support he needed to dispel the fears of the British and the white settler population.. Shortly before decolonization, Kenyatta addressed his toughest audience: the fiercely anti-independence white settler population. “I have suffered imprisonment and detention, but that is gone and I am not going to remember it,” he began, to the relief of his apprehensive white audience. “We want you to stay and farm well in this country: that is the policy of this government,” he concluded. When Kenyatta reached the end of his speech, the whites joined him in chanting his favorite slogan: “Let’s All Pull Together.” Thus a collective amnesia was born that would take years to undo. Yet, some Kenyans continued to fight for the ability to publicly articulate their own narrative, wielding language and memory rather than guns.