In a brief speech at an investment conference in London on July 26th, Mario Draghi, head of the European Central Bank (ECB), stated simply “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the Euro.” The response was phenomenal. Indexes around the world rallied, bond yields on the debt of beleaguered Eurozone countries sank while equities rocketed.

Nothing had changed. No miraculous panacea of a policy had been unveiled, no unheralded positive data released. Yet, people were buying. Moreover, they have carried on buying.

Over the past few months, major markets have climbed to record highs. September saw the Standard & Poor Index jump to within 6% of its highest value ever, while the FTSE 100 soared toward 6000 points.

This has, ominously enough, been accompanied by record lows in volume (that is, the number of shares which change hands on a given market). Even to the uninitiated, this suggests a precarious state of affairs: a teetering tower of value propped up by empty statements by politicians and policy-makers.

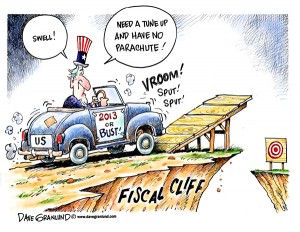

How much longer can this last? The FTSE stalls a little way off 5800, exorbitantly high for an index based in a country threatened with a triple-dip recession. The S&P and Dow Jones, having backed off the hysterical highs seen in September, have suddenly dropped below key price supports. Yields on 10-year US Treasuries fell hard after Obama’s re election, signalling deep discomfort with the next great challenge in the international financial calendar: the looming US fiscal cliff.

In the previous “Interview With A Trader”, the Globalist set out to uncover the mysteries of the market in an in-depth interview with a professional trader. Faced with a market buoyed by vaporous enthusiasm, a global economy still in turmoil, and nothing but further challenges down the road, this time the question is “What does all this mean?”

Mark, private investor and market expert, pauses before offering a cautious “It’s interesting. And, indeed, rather confusing.” Rather than trying to comment on market sentiment, he offers a more abstract explanation:

“What I’m seeing is that when shares go up in price people tend to accumulate over time: you buy 100 shares in company X at £1. It then carries on going up, so you buy more. Finally, you’re at a level where the share is worth £10 and you’re holding a large amount of stock, just accumulated in bits.”

When people are doing this and market is going up, generally there’s a mixture of stocks going up and down, he says. However, it’s a different story when fear starts to rise:

“People don’t tend to let shares go in the same way that they buy, they tend to get rid of the whole lot – it’s human nature really. It’s markets being led by two powerful things: fear and greed. Greed is a bit more drawn out and tends toward more of a crescendo, whereas fear is more of a huge stiletto spike in the back!”

This is the situation Mark sees as underpinning current market highs – stocks cautiously accumulated on wave of optimism backed by nebulous policy-maker statements. Surely, I venture, investors must be a little jaded with the number of announcements which have amounted to, essentially, nothing. Mark responds that current optimism has perhaps more grounding than my initial analysis suggested. Our discussion took place in the wake of two major monetary policy announcements. Most significant was the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)’s long-awaited announcement of another round of US Government bond buying, a project known as “Quantitative Easing”. A week earlier, the ECB also unveiled a new asset-purchasing policy, labelled “Outright Monetary Transactions” – a further step toward direct intervention by the ECB in the floundering Eurozone debt market, committing to purchasing “unlimited” amounts of Eurozone sovereign debt on a secondary market.

Mark thinks these pro-active policies are reassuring to investors:

“They do seem to stepping up to the plate, saying we will push the rules to prevent the breakup of the Euro and to protect European economies. They’ve made a very clear stance and actually put their money where their mouth is.”

However, he adds a caveat to any naive view that, economically, we’re in the clear:

“The volatility of the market becomes self-perpetuating because there’s money to be made. I don’t see short-selling or dumping stocks on the basis of unhelpful or negative announcements as any less likely – people have become conditioned to think that if Draghi is non-committal about central bond buying, there’s money to be made short selling that day. Consequently, the market goes down.”

This almost Pavlovian response begs the question: do investors really believe in the project of asset purchases? Do they care? Or is it more the case of translating macro-economic information into “Up” and “Down” signals, regardless of the efficacy or relevance of their content?

The response is initially simple: “The market will always pick up on policy statements like those because it’s a bullish [positive] signal”. However, he goes on to add that coming to the market with asset purchases does a number of things. In Europe, it’s a question of supporting bond markets, keeping borrowing costs low and allowing economies to spend their way out recession. However, in the US, the focus is more on supporting retail banks in offering low rate mortgages to try and kick-start the housing market.

“Those two things have been very useful short term for sentiment purposes and indeed for the real economy; it’s not just an academic exercise.”

However, Mark is circumspect, pointing out that growth can’t be supported in such “manufactured ways.” It’s just not feasible to carry on these projects indefinitely, he says – it becomes inflationary which, as history has taught us, can be catastrophic. The measures should “produce the necessary escape velocity to move on with real organic growth in the economy, which is what will actually propel stocks and risk appetite higher.”

This has been pivotal to the rhetoric of the entire ‘Easing’ project: it is a temporary measure, mainlining liquidity into recalcitrant economies. However, policy-maker attitude has shifted over the last few months. The FOMC have committed to continued asset-purchases for a “considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens.” Mark is sceptical of this, particularly in relation to the tenuous heights of the market:

“The worrying factor is the possibility that the nascent housing boom in the US and all the related multiplier effects are based on a house of cards. If stimulus has to be pulled away, things could become extremely difficult, extremely quickly.”

Emphasising that this does not constitute financial advice, Mark suggests that the markets are simply too high, riding on a “saccharine rush” of stimulus. Sceptical of how long positive sentiment can last in this environment, Mark turns to the next hurdle on the road to global economic stability. Regarding the fiscal cliff with a vigilant wariness, he remarks that he’ll be “watching extremely carefully and so, I think, should the rest of the world whether they’re traders or not.”

However, as ever, there are no hard and fast rules. Ever-aware of the precociousness of the market, Mark recalls the Keynsian adage: “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” In a phrase, the best strategy seems to be “hold on tight.”