“They’re beyond a terrorist group,” said United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) to the press in late August of last year. “They marry ideology, sophistication of strategic and tactical military prowess; they are tremendously well-funded. This is beyond anything that we’ve seen. So we must prepare for everything.”

“They’re beyond a terrorist group,” said United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) to the press in late August of last year. “They marry ideology, sophistication of strategic and tactical military prowess; they are tremendously well-funded. This is beyond anything that we’ve seen. So we must prepare for everything.”

The scene is the White House Press Briefing room, a serene but regal space with deep-blue walls and two large American flags flanking the podium. Directly behind the podium where Hagel is standing is the presidential seal, the symbol of what most would consider the most powerful office on Earth. With pens poised and iPhones at the ready, the White House press corps (of West Wing fame) listen to Hagel’s words, which sound more like lines out of an action-thriller film than a description of a military engagement or government information disclosure.

In November of 2014, Hagel stepped down as Defense Secretary reportedly as a result of his inability to work with the President on a strategy for ISIS. But not before his aforementioned thirty-second sound bite has been picked up and mercilessly replayed by nearly every news network in the US. Made to excerpt in nearly any TV segment and fit to print, the words, “This is beyond anything that we’ve seen” are vague, but not too vague to evade the image of a heroic soldier’s dramatic monologue before battling an insurmountable enemy. Hagel’s remarks are not only apocalyptic in tone, but they also fail to provide his audience with any meaningful information about the very real threat posed by Hagel.

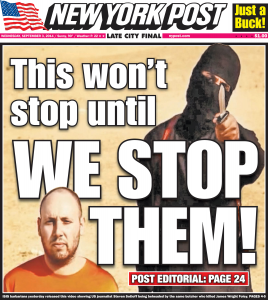

Take the September 3rd, 2014 front cover of the New York Post (pictured left.) The Post is a tabloid: it represents one of the most extreme, skewed representations of ISIS in the media. The chilling irony of American newspapers using still shots of ISIS’s own propaganda as a tool to incite public fear aside, the cover is reductive and problematic for several reasons. The language is simplistic, designed for its shock value and marketability. With it, the Post subliminally prods the consumer to regain a small, ultimately illusory semblance of control by forking over the money to buy the issue. It’s no coincidence that the letters in the words “WE STOP THEM” are larger than the victim’s face, obscuring and hijacking his story. (His name, by the way, was Steven Sotloff. He was an Israeli-American journalist who risked his life covering politics in Syria and Libya for Time magazine and The Jerusalem Post.)

By painting the face of ISIS as a masked man with a knife pointing directly at the reader, emblazoned with the block-letter headline, “This won’t stop until WE STOP THEM!”, the Post succeeds only in kindling fear and misaligning the public’s view – the view of a terrorist organization that remains much more likely to wreak havoc in Iraq and Syria than on British or American soil. And though the Post is likely an extreme example, it is all too easy to see that this is the pitfall of far too many press organizations covering ISIS. At the root of this cycle of disingenuous language lies the public consciousness of our modern society – it would be wrong to blame this entirely on profit-hungry media organizations and executives. Jeff Lewis, journalist and author of the book Language Wars: The Role of Media and Culture in Global Terror and Political Violence explained it this way:

“While some newspapers and journalists may consciously seek to inculcate particular political perspectives, more often they are working from a set of beliefs or ‘knowledge systems’ to which they subscribe without full awareness – they are unconscious reproductions of pre-existing cultural knowledge. Thus, any given event or phenomenon – including ISIS – becomes interpreted and analysed according to these pre-existing systems … it accords with a relatively standardized condition of social anxiety about Islamism and Islamic militantism.”

In other words, the language we use to describe modern-day terrorist organizations is a result of knowledge continually reinforced by the tools of today’s media – television, newspapers and the Internet. All of these mediums, which represent the genesis of our information revolution, encode the way we talk about past and current events alike. In her book The Argument Culture, Deborah Tannen posits that this type of language is particularly damaging because it limits the imagination of the reader. The result can be anything from incendiary language to jarring discordancy. In August and September, British papers were responsible for dubbing the infamous executioner in the ISIS beheading videos “Jihadi John,” a jaw-dropping, blasé and tongue-in-cheek nickname that sounds more like the name of an action figure one might find in a toy store rather than a terrorist who commits heinous murders on camera. The clever alliteration removes the political and emotional weight of the ISIS’s actions and trivializes their actions– to us, it appears as if anyone can become ‘Jihadi John’. Whatever their motives, in this regard The Daily Mail or The New York Post might as well sign itself up to be a wing of ISIS’s PR team. Fear is not just an unfortunate by-product of today’s saturation coverage: it is deliberately fostered by them.

And what of it? For one thing, Islamophobia becomes even more rampant and dangerous. The battle fought daily by British, American, and Australian Muslims becomes perceptibly more difficult with each piece of press that reductively amplifies the zealous nature of ISIS’s radical Islamic jihad, and the dangers it poses to Western citizens. The result is often taut with tangible fear and tension. During the siege of a Sydney café that left two hostages and a gunman dead last month, there were reports of an Islamic flag displayed in the café’s window. Public attention immediately turned to ISIS, and press coverage was saturated with images of the flag with Arabic writing. The next day, the hashtag ‘#IllRideWithYou’ began trending on Twitter as a way for Australian citizens to show solidarity and support for Muslims on public transportation, whose personal safety typically become even more precarious after violent incidents and incendiary press coverage. The hashtag soon caught fire and its use spread to other Western nations, becoming a symbolic stand against Islamophobia.

In addition, by sidestepping their responsibility to present the conflict in all its complexity, the press inadvertently takes the easy way out. Language becomes dichotomized beyond reality, and media coverage on both sides of the conflict dissolve into what Jeff Lewis calls “propaganda wars.” Perhaps this is inevitable: all wars require an “us” and a “them,” but there is also something especially troubling about this paradigm for it has largely taken the place of a nuanced and intellectually responsible analysis of conflict within the Middle East, one in which the perspectives of local actors are given due credit. On November 10th of last year, The Guardian quoted President Obama as saying there is “no end in sight” to the war against ISIS.” The truth is that large segments of our mainstream media are ignoring the fact that citizens in Iraq and Syria are turning to ISIS not out of genuine conviction, but because of their loss of trust in the repressive and sectarian governments in Baghdad and Damascus.

Unfortunately, whenever the US press attempts to goad President Obama into taking some sort military action, journalists resort to their time-honoured tactics of misrepresenting the situation on the ground, appealing to cultural stereotypes and substituting nuanced analysis for reductive slogans. On Fox News, one reporter went so far as to question the President’s masculinity by asking him to ‘act like a man of the house’ and ‘Step up and protect your family here in the United States, before it’s too late!’ before a press conference detailing a new Middle East policy initiative.

The more one finds examples of this issue in the press, the more hopeless the situation seems – often, it appears that we are unable to alter our language systems or ideological predispositions. But we must remember that ‘Isis’ was an Egyptian goddess and (much later) a river and student publication in Oxford before it attained its present notoriety. It is not enough for us to blame Rupert Murdoch and the Daily Mail – we must also consider our own use of words carefully. There is nothing ‘Islamic’ about ISIS at all, and the vast majority of their victims are Muslims attempting to stake out a living for themselves in this complex and diverse region, so there is no reason for us to play into their propaganda by treating the group as representative of Muslim opinion in any way. By pinpointing the dangers of media fear mongering wherever possible, we can and must reduce the popular misconceptions and cultural stereotypes that are currently so prevalent.